His Life

A biography of Joseph Bologne by biographer Gabriel Banat

Saint-Georges [Saint-George], Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de

Gabriel Banat

Published in print: 20 January 2001

Published online: 2001

(b Baillif, Guadeloupe, Dec 25, 1745; d Paris, June 9, 1799). French composer and violinist. He was the son of a Guadeloupe planter, George Bologne, and his African slave Nanon. Although his father called himself ‘de Saint-Georges’, after one of his properties, he was officially ennobled only in 1757, when he acquired the title of Gentilhomme ordinaire de la chambre du roi. (Some biographers have mistaken him for Pierre Boullongne-Tavernier, controlleur général of finance, whose nobility dated back to the 15th century; such confusion originated with de Beauvoir’s novel of 1840.) In 1747 George Bologne was accused unjustly of murder and fled to France with Nanon and her child to prevent their being sold. After two years he was granted a royal pardon and the family returned to Guadeloupe. In 1753 George took Joseph to France permanently.

At the age of 13 Saint-Georges became a pupil of La Boëssière, a master of arms, and excelled in all physical exercises, especially fencing. When still a student Saint-Georges beat Alexandre Picard, a fencing-master of Rouen, who had mocked him as ‘La Boëssière’s upstart mulatto’, and was rewarded by his father with a horse and buggy. On graduating, at the age of 19, he was made a Gendarme de la Garde du Roi and dubbed chevalier. After the end of the Seven Years War, George Bologne returned to his Guadeloupe plantations, leaving his son with a handsome annuity. The young chevalier became the darling of fashionable society; all contemporary accounts speak of his romantic conquests. In 1766 the Italian fencer Giuseppe Faldoni came to Paris to challenge Saint-Georges. Faldoni won, but proclaimed Saint-Georges the finest swordsman in Europe.

Nothing is known of Saint-Georges’ early musical training. However, after 1764, works dedicated to him by Gossec and Lolli suggest that Gossec was his composition teacher and that Lolli taught him violin. Saint-Georges’ technical approach was similar to that of Gaviniés, who may also have taught him, but Fétis’s claim that he studied with Leclair is mere conjecture. In 1769 he became a member of Gossec’s new orchestra, the Concert des Amateurs, at the Hôtel de Soubise, and was soon named its leader.

Saint-Georges made his début as a solo violinist with the Amateurs in 1772, performing his first two violin concertos op.2 to critical acclaim. These concertos reveal him to have been a prodigious virtuoso. The solo parts make extensive use of the highest positions and the composer revels in the possibilities of the newly invented Tourte bow, with bold, détaché strokes and intricate batteries and bariolage. But virtuosity was not his principal aim. The slow movements of the concertos are songful and expressive, with occasional touches of Creole nostalgia. When Gossec became a director of the Concert Spirituel in 1773, Saint-Georges was appointed musical director of the Amateurs, which rapidly became one of the best orchestras in Europe.

After his father’s death in 1774, Saint-Georges’ annuity stopped and music became his livelihood. Between 1773 and 1779 he published most of his instrumental music, including two sets of string quartets (some of the first in Paris), a dozen violin concertos and at least 10 symphonies concertantes, becoming a chief exponent of that new, intrinsically Parisian genre. Like the string quartets, the symphonies concertantes have only two movements, while the violin concertos have three.

In 1776 a proposal to make Saint-Georges music director of the Paris Opéra was blocked by a quartet of its leading ladies, who petitioned Queen Marie Antoinette to spare them from ‘degrading their honour and delicate conscience by having them submit to the orders of a mulatto’. To defuse the scandal, Louis XVI nationalized the Opéra. A year after his first serious setback due to his colour, Saint-Georges presented his first opera, Ernestine, at the Comédie-Italienne. The critics praised the music but predicted that it could not overcome the weak libretto; it did not survive its première. Undaunted, Saint-Georges abandoned composing instrumental music to devote himself to operas. Mme de Montesson, morganatic wife of the Duke of Orléans, engaged him as music director of her private theatre and, as an added incentive, appointed him Lieutenant de chasse of the Duke’s hunting estate at Raincy. His opera La partie de chasse (1778) was performed there, while L’amant anonyme received its première at Mme de Montesson’s theatre in 1780.

In January 1781 the Amateurs were disbanded, owing to financial losses incurred during the American War of Independence. Soon after, Saint-Georges founded the Concert de la Loge Olympique, part of the exclusive freemason club La Loge Olympique. As its fame increased, the orchestra moved from the Palais Royal to larger quarters at the Tuileries. It was for this ensemble, at the behest of the Loge’s grand-master, Baron d’Ogny, that Saint-Georges commissioned Haydn’s Paris symphonies.

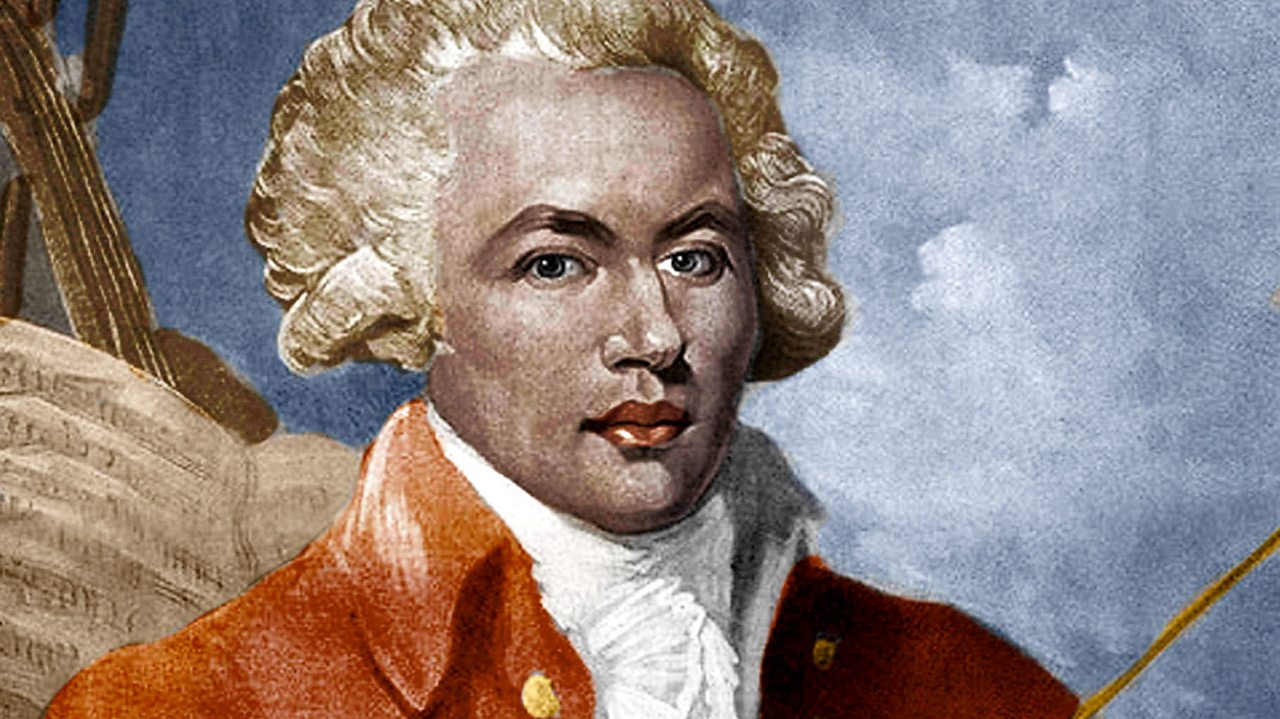

On the death of the Duke of Orléans in 1785, Saint-Georges lost his position in that household. In 1787, invited by the fencing-master Angelo, he went to London, where he gave exhibition fencing matches, including one at Carlton House before the Prince of Wales; a painting by Robineau shows Saint-Georges fighting the enigmatic transvestite ‘La Chevalière’ d’Eon. The prince also commissioned the young Bostonian Mather Brown to paint Saint-Georges’ portrait. When asked if it was a good likeness the composer replied: ‘Oh Madame, so good, it’s frightful!’ (see illustration). Returning to Paris, he composed and produced his most successful comedy, La fille-garĉon, and resumed work at the Loge Olympique.

Saint-Georges was introduced to the revolutionary circle around the young Duke of Orléans (later Philippe-Egalité) by Laclos and Brissot, founders of the abolitionist Société des Amis des Noirs, and joined the duke and Laclos on their 1789 journey to London. The following year he undertook a tour of northern France with the actress Louise Fusil and the horn player Lamothe. In Belgium he was denounced as an agent for Philippe-Egalité and expelled from Tournai by the French émigrés there. Bedridden by a long illness in Lille, he wrote his last opera, Guillaume tout coeur, for that city. He also joined the National Guard, and in 1792 the Paris Assembly made him colonel of the Légion des Américains et du Midi, which comprised ‘citizens of colour’ (including Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, father of the novelist Alexandre Dumas père). Saint-Georges was accused of misconduct but managed to clear his name, going on to help save Lille from a counter-revolutionary plot by General Dumouriez. However, in November 1793 he became a victim of the Reign of Terror and spent 18 months in the military prison of Hondainville near Clermont-sur-Oise. Freed after the fall of Robespierre, the mulatto colonel fought a long battle to regain his regiment, ending with an order to avoid Arras, its garrison town.

In 1795 Saint-Georges sailed with Lamothe to Saint Domingue, which was in the grip of a slave revolt. Having been given up for dead, they returned to Paris two years later. Saint-Georges directed another orchestra at the masonic Cercle de l’Harmonie, according to the Mercure ‘leaving nothing to be desired as to the choice of works or the superiority of the execution’. He died in 1799, of an ‘ulcerated bladder’.

Works

printed works published in Paris unless otherwise stated

Stage

PCI Paris, Comédie-Italienne

Ernestine (oc, 3, P. Choderlos de Laclos, after Mme Riccoboni), PCI, 19 July 1777, excerpts pubd

La partie de la chasse (oc, 3, Desfontaines), PCI, 12 Oct 1778, lost

L’amant anonyme (comédie mêlée de ballets, 2, after Mme de Genlis), Paris, Mme Montesson, 8 March 1780, F-Pn, ov pubd as no.2 of 2 symphonies, op.11 (1799)

La fille-garĉon (oc, 2, Desmaillot), PCI, 18 Aug 1787, lost

Aline et Dupré, ou La marchande de marrons (children’s op, 2), Paris, Beaujolais, 1788

Guillaume tout coeur, 1790, lost

Excerpts in Recueil d’airs et duos, Pn [incl. 4 from Ernestine]

Doubtful and spurious works

Le droit de seigneur (?Saint-Georges, ?after Beaumarchais), ?perf. privately, 1 aria by Saint-Georges pubd as no.3 in Journal de harpe, 1784

Other Works

Orchestral

2 vn concs., G, D, op.2 (1773), the first pubd as ‘no.1’, then as op.10 (1777)

2 vn concs., D, C, op.3 (1774)

Vn Conc., D, op.4 (1774)

2 syms concertantes, C, B, 2 vn, op.6 (1775)

2 vn concs., C, A, op.5 (c1775)

Vn conc., no.9, op.8 (1776)

2 syms concertantes, C, A, 2 vn, op.9 (1777)

Vn conc., op.11 (1777)

2 syms concertantes, E♭, G, 2 vn, op.12 (?1777), the second repr. as no.13 (1782)

2 syms concertantes, F, A, 2 vn, va, op.10 (1779)

2 vn concs., A, B♭, op.7 (1782)

2 syms, G, D, op.11 (1799), no.1, spurious, no.2, ov. to L’amant anonyme; Bn conc, lost, perf. at Concert Spirituel, 28 March 1782

Sym concertante, D, CH-Bu, parts missing; Sym concertante, G, incipit quoted by Sarasin in thematic catalogue, Bu

Chamber

6 qts, Au goût du jour, op.1 (1773)

6 quartetto concertans (1777)

6 qts, op.14 (1785), ?lost

3 sonatas, hpd/pf, vn obbl (1781)

6 sonatas, vn, vn acc. (1800), only 3 pubd; 6 airs variés, vn, vn acc., lost (mentioned by Gerber); Recueil de pièces, pf, vn [ded. Countess de Vauban], erroneously called ‘Trios’, F-Pn; Sonata, fl, hp, Pn; Adagio, pf (1978)

other works in contemporary anthologies